Is Authoritarianism forever in Turkey?

By Halil M. Karaveli (vol. 7, no. 4 of the Turkey Analyst)

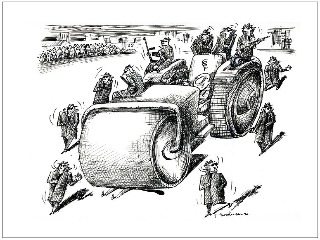

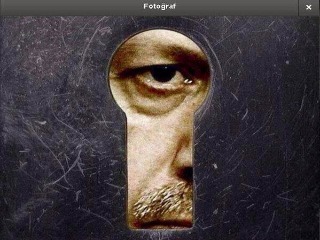

Authoritarianism has remained a permanent feature of the Turkish polity since the founding of the republic. Authoritarian rulers who have gone too far in their abuse of power are showed the door by the electorate, but the structure from which authoritarian power emanates – an all-powerful state – remains intact. The civil war that rages among the ruling Islamic conservatives bolsters the power of the Turkish Leviathan, by demonstrating what can be achieved with “big brother” methods. In the poisonous atmosphere of mistrust and enmity that prevails in Turkey, people are not going to be predisposed to put faith in the notion of a state that is neutral and in everyone’s service; it is more likely that the eternal struggle to capture the state and deploy it to enforce parochial group interests is going to continue, sustaining authoritarianism.

A Hint of Desperation: Erdogan’s Crackdown on Free Speech

By Svante E. Cornell (vol. 7, no. 3 of the Turkey Analyst)

Since Turkish prosecutors launched a major corruption probe targeting the government in December, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has focused his efforts to prevent the release and dissemination of further incriminating evidence concerning his government and family. This has included efforts to undermine the independence of the judiciary, to stifle freedom of expression, and the peddling of various conspiracy theories. The new, restrictive amendments to laws governing the internet are undoubtedly authoritarian and repressive, but they are simultaneously a sign of weakness.

Erdogan and the Challenge of Coping with Change

By Halil M. Karaveli (vol. 6, no 21 of the Turkey Analyst)

A recent, unprecedented clash between Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç, one of the founders of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), has exposed mounting dissent within the top leadership of the AKP. This has two sources: Erdoğan’s leadership style, and an increasing, ideological divergence among Muslim conservatives. That divergence revolves around the question of how the Muslim conservatives are going to relate to and cope with change – a change that they themselves have abetted. While Erdoğan reacts with old reflexes, Arınç (and President Abdullah Gül) disapprove of conservative social engineering, and seem to understand that the Muslim conservatives’ continued political success depends on their ability to remain in tune with change.

Revolution and Counter-Revolution: Kemalism, the AKP and Turkey at 90

By Gareth Jenkins (vol. 6, no. 20 of the Turkey Analyst)

Ninety years after its foundation on October 29, 1923, the Turkish Republic is already radically different to how its founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881-1938), intended. More change seems inevitable. Since it first took office in November 2002, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) has gradually dismantled Atatürk’s ideological legacy. In its place, the AKP has introduced not a pluralistic democracy but a new form of authoritarianism.