Turkey Sees Itself as the Target of American "Imperial Designs"

By Halil Karaveli (vol. 7, no. 20 of the Turkey Analyst)

The neo-Ottomans are reverting to Kemalism. From having aspired to be the rule-setter of the Middle East, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is now exhibiting neo-Kemalist traits, accusing the Western powers of harboring imperial designs against Turkey. For Turks of all stripes assuming the worst about Western “imperialists” is natural. But that also means that the fears that their prejudices entertain risk becoming self-fulfilling prophecies.

Yesterday's Wars: The Cause and Consequences of Turkish Inaction Against the Islamic State

By Gareth Jenkins (vol. 7, no. 18 of the Turkey Analyst)

On October 7, 2014, Turkey was swept by some of the most violent civil unrest in a generation. At least 23 people were killed and hundreds injured in an eruption of Kurdish nationalist anger at Ankara’s perceived indifference to the apparently imminent capture by the Islamic State of the predominantly Kurdish Syrian border town of Kobane.

Without Constitutional Amendment, Erdoğan is Unlikely to Remain an All-Powerful President

By Kemal Kaya (vol. 7 no. 18 of the Turkey Analyst)

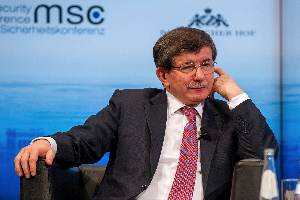

The Turkish political system is parliamentarian. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan may have succeeded in neutering of the role of the constitutionally designated executive, the government, but that is only temporary. Sooner or later, the dynamics of the political system are going to assert themselves. The prime minister, even Ahmet Davutoğlu, if he retains the post after the 2015 general election, is set to eventually reclaim power from the president.

What the Columnists Say

The question that continues to preoccupy many commentators in the Turkish press is the direction that President Erdoğan is taking Turkey. Baskın Oran, a leading political scientist and pundit, drew a historical parallel to the epochs of Atatürk and the sultan Abdülhamid II, noting that Erdoğan is copying Atatürk in his methods, while copying Abdülhamid II ideologically. Meanwhile, the statement that General Necdet Özel, the Chief of the General Staff of the Turkish military, made during the official state reception on August 30 that the military is held in the dark about the peace negotiations between the government and the Kurdish movement and that the military is going to react if its “red lines” are crossed, was welcomed in a comment in the daily Zaman. It was noted that the words of the military deserves to be listened to and that a solution that lacks the support of the armed forces does not stand any chance of success.

Looking Strong but Fragile: A New AKP and a “New Turkey”

By Halil Karaveli (vol. 7, no. 15 of the Turkey Analyst)

The appointment of Ahmet Davutoglu to head the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) represents a doubling down on the party’s Sunni Islamic ideology. But ideology alone will not be sufficient to keep the AKP in power. The self-confident ideological rhetoric that proclaims the advent of a “New Turkey” masks what is in fact a fragile economic reality. Such rhetoric is not indefinitely going to be a substitute for the kind of material progress absent which the prospects for the “New Turkey” and its power-holders look bleak.