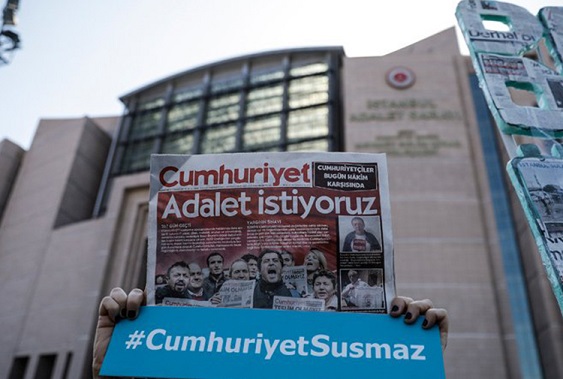

BACKGROUND: On September 11, 2017, the latest hearing in the trial against the Cumhuriyet daily newspaper was held in a courthouse in Silivri, just outside Istanbul. A total of 19 Cumhuriyet employees, including some of Turkey’s most prominent journalists, are accused of simultaneously assisting -- and in some cases also being members of – the leftist and pro-Kurdish Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), the leftist Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP/C) and the Gülen Movement, which the Turkish government claims masterminded the failed coup attempt of July 2016. Under Turkish law, all three are classed as armed terrorist organizations.

Since the case was launched in October 2016, all but six of the accused have been released pending the completion of the trial. On September 11, the presiding judges rejected an application by defense lawyers for the release of those who remain behind bars. No convincing justification was provided, either for their continued detention or for why they have been singled out from the other accused. However, it is probably not a coincidence that, in previous hearings, the six were amongst the most outspoken in describing the charges against them as being orchestrated by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in an attempt to stifle one of the few daily newspapers which is still prepared to criticize him.

Not only have the prosecutors failed to provide any evidence that the defendants supported or were involved in terrorism but the allegations appear irrational. In terms of their ideologies and ultimate aims, the PKK and the DHKP-C are diametrically opposed to the Gülen Movement. It is difficult to envisage how anyone could simultaneously support all three.

Disturbingly, in preparing the indictment in the Cumhuriyet case, the prosecutors appear to have felt little need to make the charges even appear convincing. For example, the investigative journalist Ahmet Şık is accused of trying to assist the Gülen Movement to realize its goals. However, before the movement’s alliance with the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) collapsed into a power struggle in late 2013, Gülenists in the judiciary prosecuted and imprisoned Şık for publishing details of how they were manipulating judicial processes for their own ends.

The ostensible grounds for which Şık was imprisoned then were as irrational as they are now. Gülenist prosecutors charged Şık, who is a committed leftist and a fierce critic of right-wing Turkish nationalists, with being a member of an alleged Turkish ultranationalist gang called Ergenekon, which they claimed was behind virtually every act of political violence in recent Turkish history and was ultimately controlled by the United States. (See april 4, 2011 Turkey Analyst) In a country constantly seeking solace in conspiracy theories, the claim gained considerable traction. But the absurdity of the specific charges against Şık also served a more sinister purpose. By demonstrating that anyone could be imprisoned on any pretence, without regard to logic or due process, the prosecutors were able to broaden the intimidatory impact of the Ergenekon investigation. Rather than merely punishing those they imagined to be guilty, it enabled them to terrorize those they knew to be innocent.

Long before the failed coup attempt of July 2016, the Gülen Movement had already become the AKP’s own Ergenekon. Not only was the movement blamed for virtually every setback and challenge faced by the government – including, bizarrely, cooperating with the PKK – but it, too, was alleged to be ultimately controlled by the United States. Since July 2016, the regime has broadened its anti-Gülen campaign to target anyone regarded as being associated with the movement, irrespective of whether or not there is any evidence that they committed or were aware of any criminal acts. The only exception has been inside the AKP, many of whose members were arguably considerably more complicit in the crimes committed by elements within the Gülen Movement than the majority of Gülen’s rank and file sympathizers.

Although the Cumhuriyet case has attracted the most international attention, it is not the only absurdity. Amongst the tens of thousands who have been arrested and/or stripped of their livelihoods on allegations of membership of the Gülen Movement are many – such as secularists, atheists and members of Turkey’s heterodox Alevi community – whose sympathies and worldviews could not be more different. As with the Ergenekon investigation, the absurdity of some of the allegations has served as an amplifier, terrorizing the innocent to the point where no one who criticizes or questions the government can feel safe.

IMPLICATIONS: There has also been a contrast between the regime’s insistence on the Gülen Movement’s power and pervasiveness and the selectivity of its willingness to conduct thorough investigations of the criminal acts allegedly carried out by some of its members. Sound often seems to take priority over substance, and self-aggrandizing myth over reality.

This even extends to last year’s failed coup. The government has refused to allow a comprehensive investigation of the events of July 15-16, 2016. There has yet to be even an acknowledgment of the conscripts and cadets who were tricked into participating in what they believed was an exercise – and were then lynched by Erdogan supporters. The government impeded the work of a parliamentary committee of inquiry, including refusing to allow it to talk to Chief of Staff General Hulusi Akar and intelligence chief Hakan Fidan -- presumably to prevent them from having to answer questions about their curious behavior in the immediate run-up to the putsch.

The official denials that any of those detained have been tortured or physically abused have been contradicted by a mass of evidence that is so extensive as to suggest that, rather than being the actions of a few rogue individuals, such practices have become widespread and centrally approved. This is not only problematic in itself but raises doubts about the reliability of any alleged confessions of wrongdoing – and is also a gift to anyone wishing to retract what had been a genuine confession.

Since the trials of the some of the alleged participants in the putsch began in the early summer of 2017, the emphasis has been on spectacle rather than justice, emotion rather than rational analysis. Suspects are paraded – and excoriated in the pro-government media – as if their guilt has already been determined. Hearings are frequently interrupted by impassioned outbursts by government lawyers and the bereaved relatives of the civilians who Erdogan called onto the streets to confront the putschists. Not everything in the trials is absurd. Some of the evidence presented by the prosecution – such as CCTV footage – suggests that some of the defendants are being disingenuous in denying that they actually participated in the coup. But little attempt is being made to filter out the facts from a mass of supposition, distortion and untruth.

Perhaps more insidious than the frenzy with which the pro-government media have covered the trials have been the silences. There are many anomalies in what is known about the events of July 15-16, 2016 – such as the participation of both suspected Gülenists and known opponents of the movement and why, even in a closed WhatsApp group, the putschists used Kemalist terminology to describe themselves. But there are also many missing pieces. Some may eventually turn out to be Gülen ones. But they are still missing – and no one appears to be looking for them.

One of the most curious features of the coup attempt was its incompleteness. The purported coup plan that was fabricated by elements in the Gülen Movement for the Balyoz (or “Sledgehammer”) case – which resulted in the imprisonment of hundreds of serving and retired military personnel – was flawed, but it was detailed and included provisions for what would supposedly happen if the putsch was successful. Neither of these apply to the real attempted putsch of July 2016. It is difficult to believe that the Gülen Movement would spend considerably more time and effort on an imaginary coup plot that one that they were planning to implement – which suggests that, if they were responsible, their plan has yet to be discovered.

Indeed, the specific actions taken by the putschists appear to have been more about visibility and public impact than seizing control of the apparatus of state. The limited forces that participated in the coup were certainly sufficient to cause considerable material damage and kill even more than the 250 civilians who died. But they were never going to be enough to seize power, much less to hold it.

It was common knowledge for months before the coup attempt that lists of suspected Gülenists in the military were being compiled in preparation for their expulsion. Yet, even if Gülenists had panicked and planned and implemented the putsch at very short notice with what they knew were very limited forces, this would not explain the specific events that occurred on July 15-16, 2016. If anything, it would make them even more curious.

If the attempted putsch was to have succeeded, the known events of July 15-16, 2016 can only have been a part of a much larger plan, most of which still remains unknown. The only plausible alternatives appear to be that the putschists were acting completely irrationally or that they had been given the erroneous impression that they were only part of a much larger plot. When so much still remains unclear, what is most troubling is not the lack of answers. It is the absence of questions.

CONCLUSIONS: The silences are not confined to allegations about the Gülen Movement. In fact, they are probably at their most pernicious in the regime’s control over news from the predominantly Kurdish southeast, where they are exacerbating a widespread sense (including amongst Kurds who are opposed to the PKK) that the rest of the country is indifferent to their sufferings – and further fuelling a growing conviction that the future of the region lies in some form of detachment from Ankara.

Nor is the regime’s increasing disregard even for the appearance of the rule of law only affecting its critics and opponents. It is probably having a more dangerous impact on Erdogan’s hard-line supporters. Embittered by class hatred against the more Western-looking segments of society, and empowered by what they regard as their role in thwarting the July 2016 coup, many already appear to believe that they are engaged in a form of civil war against the perceived traitors in their midst – and have not just a right but an obligation to take matters into their own hands.

Gareth H. Jenkins is a Nonresident Senior Fellow with the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center, affiliated with the American Foreign Policy Council and the Institute for Security and Development Policy.