BACKGROUND: On March 11, 2019, Turkey's Health Minister Fahrettin Koca announced Turkey's first case of COVID-19. Although this was the first case on Turkish soil confirmed by the Turkish government, at least four cases of transit passengers that had passed through Istanbul's busy international airport were confirmed to have COVID-19 when landing at their final destination.

With a comparatively strong public health care system and experience in dealing with humanitarian crisis, Turkey's state apparatus began ramping up its response, starting with the order on the following day that closed schools and universities across the country effective on March 16. Reluctant to shutdown economic activity, Ankara implemented stricter measures in a staggered manner that followed the virus to continue to spread rapidly and to vulnerable populations.

Four days after the first reported case, the Turkish government ordered the temporary closing of all bars, nightclubs, dance clubs, and similar venues on March 15, 2020 to help prevent the spread of the virus. The next day, Ankara banned communal prayers at mosques (although mosques remained open for individual prayers). Only on March 21, 2019, the government banned all citizens 65 years of age and older from leaving their homes.

On March 27, the government placed 41 localities in 18 provinces under quarantine. To discourage public gatherings in Istanbul, the 'epicenter' of Turkey's COVID-19 outbreak, Turkey's interior ministry closed down parks and coastal areas as well as suspending inter-city buses and ferry service. However, no stay-at-home orders were issued for Turkey's largest city and commercial engine.

Istanbul encapsulates the Turkish government's dilemma. While over half of Turkey's COVID-19 are in Istanbul, the economic activity of the city with it 16 million inhabitants generates 30 percent of Turkey's gross domestic product (GDP). Quite simply, Turkey cannot afford an economic shutdown in Istanbul.

Yet with virus spreading out of control, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan appeared on national television on April 3, 2020 to announce a 15-day travel ban to 31 of Turkey's 81 provinces, the mandatory wearing of masks in public places, and a general stay-at-home order for those under 20 years of age.

Given the prior examples of Iran, Italy, and Spain, Turkey had ample warning to take these more comprehensively strict measures from the outset. Indeed, witnessing the humanitarian tragedy unfolding in Iran, Ankara closed its land border with its eastern neighbor on February 23, 2020. The first cases of COVID-19 in Italy and Spain were reported on January 31, 2020 and all of Italy was placed under quarantine by March 9, 2020. Similarly, Spain imposed a national lockdown on March 14, 2020.

By the time of the April 3 order, Turkey had one of the world's steepest growth curves for the spread of the virus. Turkey ranked 9th in the world for total COVID-19 cases and 12th overall for total COVID-19 deaths. At the time of publication, Turkey's COVID-19 fatality rate was six times lower than Italy's rate and more than five times lower than that of Spain. It is possible that Turkey may avoid a similarly high total number of fatalities due to its more youthful population. Turkey's median age of 31.5 years is significantly lower than Italy's median age of 47.3 years and Spain's 44.9 years. However, several medical conditions that raise the risk of death, such as diabetes, are prevalent in Turkish society. The steady daily rise of Turkey's fatality rate remains a cause of concern.

IMPLICATIONS: While Turkey will weather the health crisis caused by COVID-19, it is less clear how Turkey will cope with the economic cost of the virus, especially as the global economy will likely take at least one and a half to two years to rebound to its pre-COVID-19 level.

Turkey's economy was already severely ailing before the COVID-19 outbreak, with its 2019 economic growth falling below 1 percent. Suffering under long term structural problems, Turkey's low 2019 economic growth was worsened by the 2018 currency shock as well as new overseas military operations in Syria and Libya. Turkey only avoided recession in 2019 through Turkey's central bank transferring on 40 billion Turkish Lira in legal reserves (equivalent $6.6 billion) to the national budget.

With declining revenues amid greatly increased military spending on operations in Syria and Libya, Turkey has already tapped an additional 20 billion of reserves in the first quarter of 2020 alone to attempt to halt the country's currency slide. On April 3, 2020, when President Erdoğan implemented Turkey's more severe restrictions, the Turkish Lira traded at 6.74 to the U.S. dollar, a weakening of the Lira not seen since the 2018 crisis.

Turkey's economic stagnation occurred despite the fact that its exports increased by 1.9 percent in 2019 compared with the previous year. Turkey's exports, which accounted for close to 30 percent of its GDP, will suffer enormously as a result of the economic downturn in Europe and other areas stricken by COVID-19.

In 2019, the EU27 was Turkey's leading export market, accounting for 42.4 percent of Turkish exports. The value of Turkey's total exports to the EU27 amounted to € 68.3 billion (equivalent to about $69 billion in current U.S. dollars). With the EU27 likely to be in recession for the rest of 2020 and throughout most of 2021, Turkey is facing a severe revenue loss from its major export market.

Turkey's next five top expert markets in 2019 were the United Kingdom (6.2 percent), Iraq (5.7 percent), the United States (5.0 percent), Israel (2.5 percent), and Russia (2.3 percent) Accounting for 21.7 percent of Turkey's export market, Ankara can expect a similar decline in export earnings, exacerbated in Iraq’s and Russia's cases by low oil prices.

The rest of Turkey's top ten export markets are, in order, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Iran – accounting for 7.2 percent of Turkey's export market. Although lower energy prices will provide Turkey with some relief, it also means that at least six of its top export markets will be even less capable of purchasing Turkish exports, driving down export revenue.

In addition to the roughly 30 percent earned from exports, Turkey's massive tourist industry accounts for 12 percent of its GDP. Turkey's peak tourist season, which runs from mid-April to mid-September, will likely return a fraction of its usual revenue in 2020, directly reducing the spending power of approximately 2 million workers.

The decline in exports and tourism, accounting for close to half of Turkey's GDP, will have a downward cascading effect as domestic consumer demand declines. In 2019, Turkey already had a population of 4.5 million unemployed working-age citizens. The government's 100 billion Turkish Lira "economic stability shield," announced on March 18, will not solve the problem. Although designed to be an economic stimulus package, the roughly $15 billion initiative consists primarily of tax cuts and payment deferrals for businesses and will not put enough cash in the hands of consumers to prop up domestic consumer spending.

Turkish workers, who have worked 600 days in the past three years, are entitled to three months of financial assistance from the Unemployment Insurance Fund, if the businesses for which they worked are forced to close. The government has now reduced the qualification requirement to 450 days employment. However, the 150-day reduction like the additional $307 million allocated to Turkey's government-run social assistance programs are inadequate to prevent consumer demand from drastically shrinking.

The government will need to provide a massive injection of cash into Turkey's economy. As a result, on March 31, 2020, the Turkish government began printing more money. This move will further drive down Turkey's already low crediting rate and drive away desperately needed long-term foreign direct investment. Rating agencies have warned that Turkey's economy will be the hardest hit among the G-20 economies. Predicting the Turkish economy will enter a deep recession, Moody's stark forecast expects “a cumulative contraction in second- and third quarter GDP of about 7 percent.”

CONCLUSIONS: Ankara is fighting an unwinnable three-front war: against the COVID-19 pandemic, an extensive military commitment in Syria and ongoing operations in Libya. Although the foreign sponsors of Turkey's adversaries in these theaters will be similarly affected by COVID-19, Russia's permanent bases and large troop presence in support of Bashar al-Assad’s government in Syria and the United Arab Emirates’ massive re-supply of Khalifa Haftar's Libyan National Army provide Turkey's rivals with an advantage over the long term as the economic effects COVID-19 take their toll. Thus, Turkey finds itself in a use-it-or-lose-it position in Syria and especially Libya, which cannot be directly resupplied over land.

With its underlying resilience, Turkish society will ultimately cope with COVID-19. However, in the short term, the current level of Turkey's foreign military interventions is economically untenable. To cope with COVID-19 while securing recent geopolitical gains for the long term, Ankara is actually likely to intensify its overseas military operations, particularly in Libya, in the immediate term to ensure an enduring strategic stalemate with its adversaries.

AUTHOR’S BIO:

Dr. Michaël Tanchum is a senior associate fellow at the Austrian Institute for European and Security Studies (AIES), a fellow at the Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace, the Hebrew University, Israel, and non-resident fellow at the Centre for Strategic Studies at Başkent University in Ankara, Turkey (Başkent-SAM). @michaeltanchum

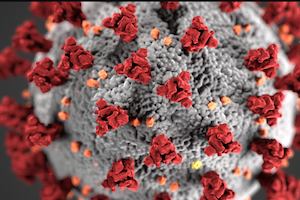

Image Accessed 4.13.2020