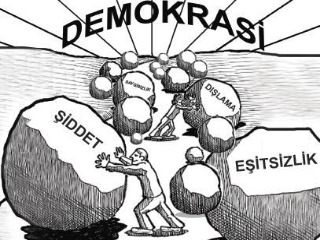

BACKGROUND: The fundamental problem of the democatization efforts under the rule of the AK Party is its pragmatic approach: democracy is supported as long as it helps the AK Party consolidate its power. In the view of the AK Party, which came to power in 2002 promising democratization and supporting the EU accession process in order to push the military out of the politics, democracy is a gift to be presented rather than a necessary need; that became clear in 2011, after the party consolidated its power following its third consecutive electoral victory. Therefore, it is no surprise that the AK Party’s democratization package, which was announced on September 30, 2013, fell short of the expectations of many in Turkish society.

The package was expected to address the Kurdish issue, as a peace process was started between the Turkish state and the outlawed Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) in late 2012. According to the package, Kurds are promised three main reforms. First, education in Kurdish language will be allowed in private schools. This means that there will be no public schools providing Kurdish language education. In other words, Kurds, who do not have sufficient means, will still have to send their children – who in many cases do not know any Turkish – to public schools in which the medium of education is Turkish.

Secondly, the package promises to change the electoral system. According to the current system, there is a nationwide threshold to the parliament and political parties must receive a minimum of 10 percent of the total votes in order to gain seats in the parliament. This has been a disadvantage for the Kurdish political parties, which get approximately 6-7 percent of the total votes. Instead of the current system, the AK Party’s package offers to lower the threshold to 5 percent, coupled with the introduction of narrow constituencies. The AK Party’s offer is designed to help the Kurdish political parties to gain more chairs in the parliament while at the same time ensuring that the AK party itself does not suffer a reduction in its number of seats in the parliament.

One can argue that the AK Party’s package just eliminates a formal obstacle that in practice has been circumvented anyway; Kurdish politicians were elected as independent candidates in the 2011 elections and formed a parliamentary group of the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP) after they joined the parliament. Nevertheless, the Kurdish movement and the Kurdish electorate were expecting Ankara to take concrete steps that would have devolved at least some measure of autonomy to the Kurdish populated areas. This did not happen.

Finally, the package allows the letters “x”, “w” and “q” to be used in Kurdish words and the original names of the Kurdish villages, which were re-named after the foundation of the republic in 1923, are to be re-instated.

IMPLICATIONS: In the final analysis, the democratization package is far from satisfying the Kurds; its main objective is to secure the AK Party’s grip on power in the political system, rather than to bring a solution to the long lasting Kurdish problem. Since the AK Party is heavily supported by voters on the right wing of the political spectrum, who tend to be strongly Turkish nationalist, any concrete attempt to meet Kurdish expectations such as offering local autonomy, not to speak of introducing a federal system, would undermine the popularity of the AK Party, pushing rightist voters to the Nationalist Action Party (MHP). Yet on the other hand, the ongoing peace process between Ankara and İmralı (where Abdullah Öcalan, the leader of the PKK, is imprisoned since 1999) has suspended the violent activities of the PKK. The end of the violence might create an opportunity for Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to present himself as the architect of peace, enhancing his standing prior to the presidential election in August 2014. However, as the AK Party has elected to try to maintain its dominant position in the current system, its Kurdish initiative is hampered and the party is prevented from initiating any fundamental reforms to resolve the Kurdish question.

In addition to the Kurds, the AK Party’s democratization package also aims to regain the appreciation of the liberal circles. During the Gezi Protests in May and June 2013, the AK Party was accused of subscribing to a majoritarian rather than to a pluralist definition of democracy. According to some liberal intellectuals, the rule of the AK Party offers a perfect example of illiberal democracy, as it uses the power of state apparatus in order to control civil society and the economic sphere. Furthermore, liberals argue that the AK Party has no ontological problem with the omnipotecy of the state, of the strong position of the state against individuals. In criticizing the Kemalist era and philosophy, the AK Party aimed to eliminate the secular guardians such as the military, the judiciary and the mainstream media in order to capture the government, but it did not challenge statism itself.

Liberal intellectuals point out that ensuring that the government does not violate the basic liberties of individuals is more important than how the electoral system is designed. That is to say, popular support for the AK Party does not legitimize the government’s increasingly authoritarian tone and its attempt to control non-state actors.

Measured against liberal principles and expectations, it is safe to argue that the democratization package makes little or no contribution to the liberalization of Turkey. The only reforms that satisfied the liberal circles are the abolishment of morning oath of allegiance that primary school children uttered every day before classes began, and the lifting of the headscarf ban for public employees, save for the military, the police and in the judiciary.

The Turkish nationalist school oath was introduced in 1933 at the height of ethnic nationalism in both Europe and Turkey. Among liberals, it is not uncommon to assume that the text of the oath is fascist-inspired. However, it is not because of the oath ceremony that successive generations have been raised as nationalists in Turkey. What has been infinitely more consequential is the fact that the state – according to a law from 1924 – maintains a strict monopoly over education, determining the curriculum of the schools no matter whether they are public or private. It is safe to argue that the school system, including the higher education, is the crucial component of Turkey’s official “ideology machine”. Even though goverments have come and gone and curriculums have changed, the state’s monopoly over education has been permanent; it has created an “intellectual” atmosphere where critical thinking has been widely discouraged.

The abolishment of the Turkish nationalist morning oath in the schools will only seem to be a cosmetic reform as long as governments continue to use education as a tool of indoctrination. In February 2012, Prime Minister Erdoğan said that “we will raise religious youth”. The abolishment of the morning oath is a typical example of the policies of the AK Party: the party makes small, symbolic reforms knowing that they will be appreciated by liberals, but without offering liberals any real hope about democratization.

CONCLUSIONS: The AK Party’s “gift” in a package failed to meet the demands and expectations of diverse social and political constituencies, which clamor for more democracy and liberty. In addition to Kurds and liberals, otherwise apolitic seculars, who protested against Erdoğan’s authoritarian style of leadership during the “Occupy Gezi” process, were not offered any guarantees that their life styles and choices are going to be respected and enjoy protection. The package allows public employees to wear headscarves except in the workplaces that require uniform, but it does not enlarge freedom for non-conservative women: a TV hostess was recently dismissed from a private channel after Hüseyin Çelik, a deputy chairman of the AK Party, had criticized the decollete dress that she had worn on TV.

At the end of the day, the same pattern repeats itself: Democracy and freedoms are not embraced as universal principles by the AK Party. While many Turkish liberal intellectuals have engaged in a discussion whether the contents of the package make it democratic or not, the discussion instead needs to center on the AK Party’s inclination to parcel democracy up and its self-serving perception of democracy as a “gift” to be offered by a benevolent but still omnipotent state that expects the gratitude of its subjects in return.

Burak Bilgehan Özpek is Assistant Professor at the Department of International Relations in TOBB University of Economics and Technology, Ankara.