BACKGROUND:The campaign that preceded the April 16 referendum was the most imbalanced in recent Turkish history. Not only did Erdoğan and the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) mobilize the resources of the Turkish state in an attempt to persuade voters to approve the introduction of an autocratic presidential system but they used the State of Emergency, which was introduced after the July 2016 failed military coup, to try to stifle the No campaign. State officials frequently banned No campaign rallies, citing purported security concerns. But there were no bans on public meetings in favor of the proposed changes. In many places, the two camps often campaigned side by side without any friction. But there were also numerous physical attacks on No campaigners, some of which caused serious injury. Yes campaigners faced no such assaults.

In addition, the regime used its control over the now largely servile mainstream Turkish media to restrict coverage of the No campaign in favor of lavish and frequently fawning coverage of Erdoğan and the Yes campaign. Unprecedentedly, state broadcasters were explicitly told that they would not be required even to pay lip service to the usual requirement in elections and referenda that they give equal coverage to all sides.

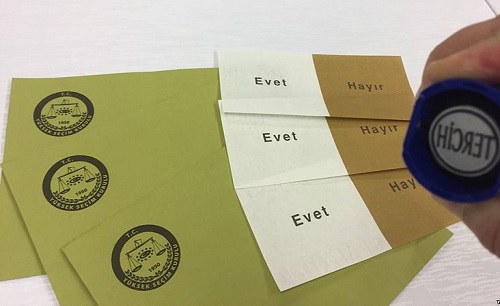

Perhaps most perniciously, the regime's control of the media enabled it to set the parameters of the public debate. Newspapers and television channels faithfully repeated the regime's characterization of No campaigners as terrorists and traitors, on the grounds that they were opposed to the introduction of a system vital to the country's peace, prosperity and international influence. Yet no attempt was made to ask the regime to explain how the proposed changes to the constitution would help resolve Turkey's many pressing problems, particularly as Erdoğan already rules as a de facto autocrat and is manifestly failing to deliver. Instead, the proposed constitutional changes were presented in unquestioning Manichean terms, a simple choice between black and white – with even the ballot papers being divided into brown for No and white for Yes, and voters asked to stamp which they preferred.

As a result, it was already difficult to argue that the referendum was free and fair even before the electorate went to the polls on April 16 – and worse was to follow. When the polling stations opened, it emerged that some had only been provided with stamps saying "Evet" or "Yes" rather than the required "Tercih" or "Preference". The Supreme Electoral Board (YSK), which oversees all voting processes in Turkey and is now dominated by political appointees, failed to provide a satisfactory explanation of how this had happened.

There were also numerous reports of election observers being harassed by security officials and, particularly in the predominantly Kurdish southeast, even being expelled from the polling stations. The reports of such incidents continued after the polls closed and the counting began. Photographs and videos began appearing on social media showing election officials entering incorrect totals on the official tally sheets. Some were probably simple human errors. Others may have been result of individual officials using their own initiative, either out of personal conviction or in attempt to ingratiate themselves with the regime. But, as the results were declared from around the country more irregularities and statistical anomalies started to emerge. More disturbing than each instance in itself, were the apparent patterns – not least that the irregularities and anomalies were overwhelmingly in favor of the Yes campaign.

Overall, the Yes campaign won by 51.4 percent 48.6 percent. But there were nearly 2,400 polling stations at which the total votes cast exceeded the total number of people who were eligible to vote there. Some of the discrepancies can probably be explained by the provision in Turkish law which allows members of the police and gendarmerie to vote at the polling stations where they are assigned to provide security rather than only at those where they are registered on account of their home address. But this does not explain instances in which the discrepancy was greater than the number of security officials at the polling stations concerned. Nor does it account for the numerous instances in which turnouts of more than 100 per cent were reported in neighborhoods where a large proportion of the registered population was not present at the time – such as in parts of the southeast where many had temporarily relocated as seasonal workers to western Turkey and were unable to vote at all on April 16.

IMPLICATIONS:Turkey’s southeastern provinces voted to reject the proposed constitutional changes by a margin of two to one. However, the turnout in the southeast was significantly below both the national average and the usual levels in the region. This is probably at least partly attributable to the repercussions of the urban war between the state security forces and the militant Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) which started in summer 2015 and resulted in the displacement of around 400,000 people – many of whom had not registered to vote in their new places of residence by the time of the referendum. More curious was the surprisingly strong ”Yes” vote – albeit still less than a majority – in many areas where support for Erdoğan and the AKP has traditionally been either very low or literally non-existent and which had been regarded as strongholds for the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). The pro-government media seized on this as proof that the Kurds are deserting the HDP and PKK for Erdoğan and the AKP. However, opinion polls in the region in the run-up to the referendum – including by companies which accurately predicted the referendum result in other parts of the country – had detected no indication of any such shift.

The official results of the referendum also showed an unexpectedly high number of invalid votes in southeast Turkey, more than twice the usual average for the region. Not only is this curious in itself – given that the simplicity of the choice between Yes and No on the ballot paper could have been expected to reduce the number of invalid votes – but it was not repeated in any other region of the country.

Taken as a whole, the referendum results suggest that the Yes side performed considerably better in rural areas than in the cities. This is probably partly attributable to socio-economic factors. In the run-up to the referendum, opinion polls had suggested that the better educated voters were, the more likely they were to vote No. Similarly, the more people self-identified as being pious or very pious, the more they were likely to vote Yes. In Turkey, people living in the countryside tend to be less well-educated and more consciously pious than their counterparts in the cities.

However, rural areas were also where levels of independent oversight of the referendum were lowest. The vast majority of documented instances of electoral irregularities and fraud – such as photographs and videos – were in urban areas, which is also where there were the highest concentrations of independent observers. But most of the statistical anomalies and curiosities occurred in rural areas where there was little non-regime oversight of the referendum. Disturbingly, the results which are most difficult to explain occurred in the region of the country where there was the least independent monitoring, namely in the predominantly Kurdish southeast. Indeed, in some rural areas in the southeast, independent monitoring was so limited as to be virtually non-existent.

Perhaps most disturbing of all was the attitude of the YSK. Under Turkish law, in order to prevent the stuffing of ballot boxes, votes are classed as invalid unless both the ballot paper itself and the envelope in which it is placed are officially stamped by an election official. However, on the evening of 16 April, when the counting of the votes had already begun, the YSK accepted a proposal from the AKP to class all ballot papers without the official stamp as being valid. This is illegal. In its defense, the YSK claimed that there were precedents. This is true in as much as there had been previously been a handful of occasions when the YSK had allowed a small number of unstamped ballot papers at specific polling stations to be classed as valid. But there was no precedent for suspending the law nationwide.

In its defense, the YSK echoed the rationale used by the AKP when it asked for the requirement to be lifted, namely that insisting that all ballot papers had to be stamped disenfranchised voters who had – through no fault of their own – been given unstamped ones. But, if this was the YSK’s only motivation, it could have simply instructed election officials to count unstamped ballot papers separately and then added them to the totals in the polling stations concerned. In this way, there would at least have been a record of how many unstamped ballot papers had been distributed and thus some indication as to whether they could have affected the overall result of the referendum. By failing to do so the YSK – which, given how tightly controlled it is by the regime, also means Erdoğan and the AKP – not only cast a shadow over the legitimacy of the referendum result but also raised questions about the legitimacy of the transition to a presidential system.

Surprisingly, the YSK even refused to investigate any of the reports of fraud and irregularities, including instances where the evidence of some kind of wrongdoing – regardless of whether it was a personal initiative or part of something much larger – appears irrefutable.

CONCLUSIONS: The constitutional referendum and the authorities’ handling of the campaign that preceded it have reinforced concerns that Turkey is descending ever deeper not only into authoritarianism but into lawlessness. Indeed, the refusal to provide the referendum result with a patina of legality – such as by promising to investigate the alleged irregularities and then declaring that no evidence of wrongdoing had been uncovered – suggests that the regime no longer feels the need to maintain even the semblance of the rule of law.

For Erdoğan’s diehard followers, his victory on April 16 was proof of his strength and resilience in the face of what they imagine are the foreign conspiracies that are constantly seeking to undermine him. In reality, it was another sign of his growing weakness, proof that – amid his continuing attempts to suppress any expression of dissent – he can no longer remain in power by democratic means.

Gareth H. Jenkins is a Nonresident Senior Fellow with the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center

Picture credit: wikimedia.org accessed on May 31st, 2017