BACKGROUND: So far, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has used cheap capital and an overvalued currency to strengthen his grip on power and to consolidate his support base. Like other right-populist leaders around the world, the Turkish leader has done so by providing benefits for his supporters. This ultimately explains the solid support for Erdoğan and his party in, for example, the low income, working-class districts of İstanbul, such as Bağcılar and Esenler.

An estimated 31 million people in Turkey benefit from social aid programs. The expansion of government social programs was in part made possible by an increase of the tax revenues. The share of indirect taxes in tax revenues, specifically consumption taxes, is relatively high in Turkey, which means that the treasury has swelled with the acceleration of economic growth. This in turn has provided the government with ample resources, part of which has been channeled to the poorest segments of society.

The vast expansion of the construction sector – the dynamo of the Turkish economy – has also contributed to higher living standards among the urban poor in the former shantytowns. Credit-fueled apartment blocks, springing up like mushrooms around the big cities have doubled and then tripled land prices in these formerly poor districts, also to the advantage of the shantytown dwellers.

The poor peasants from Anatolia, who in the 1970s populated the shantytowns of Istanbul and other big cities, were mostly left-leaning at the time. Unsurprisingly, they shifted to the conservative AKP in the 2000s as their neighborhoods became havens of new, government-subsidized apartment blocks. Many of the formerly poor have made fortunes from constructing apartment blocks on the land that they laid claim to when they arrived from Anatolia, a change vividly described by the Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk in his recent novel A Strangeness in my Mind.

The spectacular growth during the AKP era created the illusion among many supporters of the ruling party that they were experiencing a revival of the “Ottoman spirit” and “glory,” leading to an upsurge in nationalism. The fact that it was in fact the flow of hundreds of billions of dollars – a massive growth in global liquidity – as a result of the quantitative easing program of the U.S. Federal Reserve that sustained the rise of consumerism in Turkey (as in other emerging markets) escaped attention for a long time.

Turkish banks borrowed cheaply from international markets, bringing billions of dollars into Turkey, and distributed money to consumers in the form of mortgages, car loans, etc. This is how in the last ten years, new apartments even far from the city centers have found buyers for a million dollars. In such a district, Bahçeşehir – thirty miles from the center of Istanbul – real estate prices have tripled during the span of the last decade.

IMPLICATIONS: Little attention has been paid to the political consequences of quantitative easing in emerging markets. Yet it is obvious that quantitative easing has allowed populist-authoritarian regimes to consolidate their popular base. Arguably, the populist-authoritarian Turkish regime owes its stability and longevity in large measure to the policies of the Federal Reserve.

The primary aim of quantitative easing was to stabilize financial markets and to bolster economic activity in the United States. But it also led to increased capital flows towards emerging markets. And the increase in capital flows to developing countries has in turn had unwelcome political consequences.

Emerging market countries have been regarded as high return havens, given their high economic growth and comparatively higher interest rates. Since 2010, private capital flows to emerging markets have averaged $1.1 trillion. This should be compare with $100 billion net capital flow to emerging markets in early 1980s.

As a result of massive capital flows, emerging markets have achieved an average annual per capita growth rate of 5.3 percent in the last decade, rather than the historical average of 2.9 percent. Yet every fairy tale has an end. In the Turkish case, the fairy tale ended with the Federal Reserve’s decision to gradually end quantitative easing in 2014. According to the Institute of International Finance, non-resident flows to emerging markets slipped to 1.14 trillion dollars in 2018, from 1.26 trillion dollars in 2017. It estimates that flows will remain broadly stable at 1.13 trillion dollars in 2019.

However, there are significant differences among emerging countries. Most notably, flows to China are projected to rise to a record high of $580 billion in 2018, helped by increased foreign access to Chinese domestic markets. In contrast, portfolio investments in most other emerging markets have been declining. Excluding China, non-resident capital flows to emerging markets are anticipated to be around $560 billion in 2018, over 30 percent lower than in 2017.

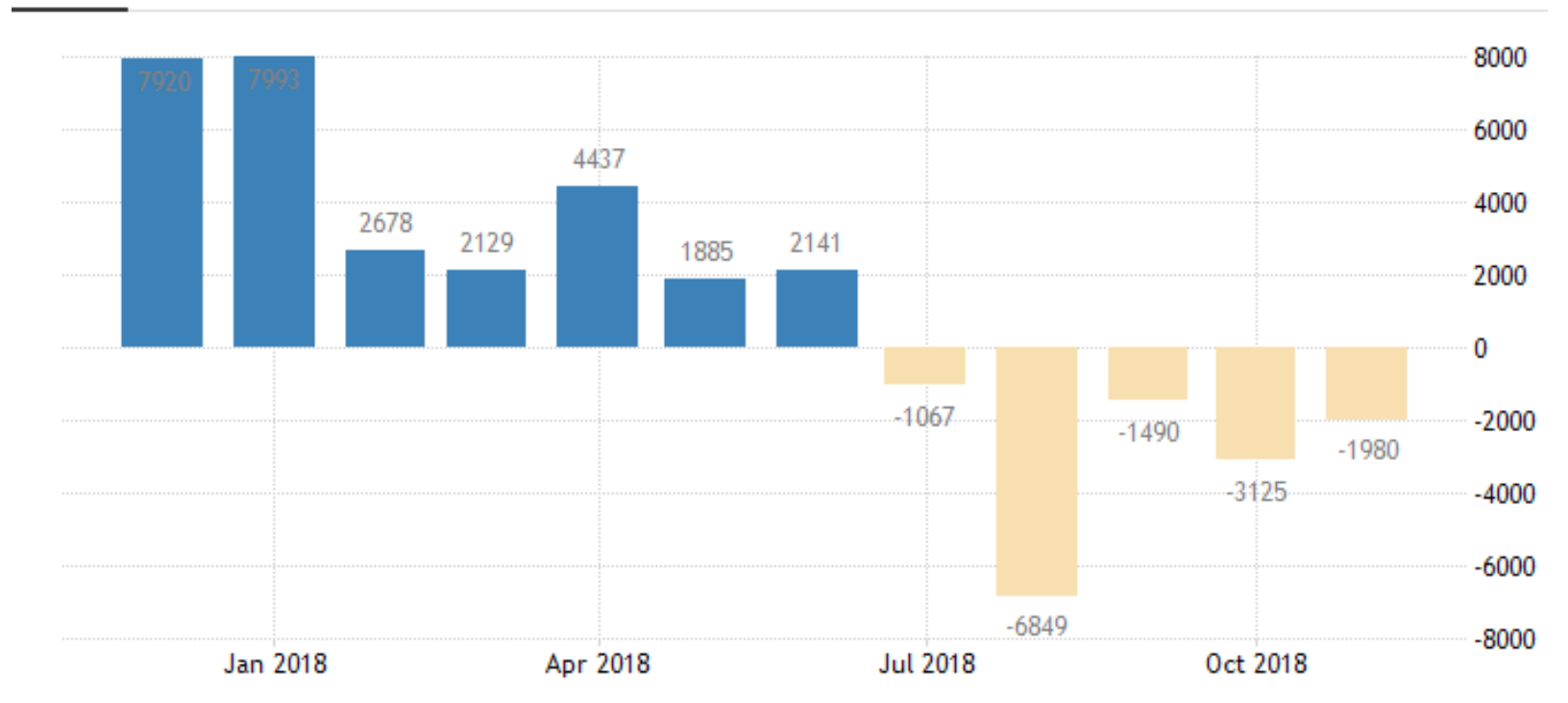

According to the World Bank, Turkey was particularly badly affected by the general move away from emerging markets due to its accumulated macroeconomic imbalances (high current account deficit, high inflation, overheating economy) and perceived policy weaknesses. In the first three quarters of 2018, capital flows to Turkey averaged a third of the inflows over the same period in the previous 5 years.

Capital Flows to Turkey

(Source: Tradingeconomics.com)

Economic activity in Turkey slowed sharply after the lira slumped against the dollar. In the absence of capital flows, the Turkish economy is expected to shrink in the last quarter of 2018 and in the first quarter in 2019. Expectations for economic growth in 2019 are either negative or static.

The New Economic Program announced by the Turkish Treasury and Finance Minister Berat Albayrak in September 2018 requires big cuts in public spending to restore macroeconomic stability. The ample resources which have been mobilized for electoral successes in the past have vaporized.

The slump in the economy directly affects the daily life of people. Turkish real wages fell substantially in the last year, as inflation soared to 26 percent, and now floats around 20 percent. Interest rates soared to intolerable levels. To take out a mortgage for 300,000 Turkish liras means paying back the bank 1,000,000 TL in ten years. It is not surprising that the construction industry has come to a halt. Auto and real estate sales dropped 30 percent in 2018.

The skeletons of unfinished constructions now surround the outskirts of İstanbul. “A promised economic revival is evaporating,” stated the Wall Street Journal in a story about unfinished construction and its victims in İstanbul.

As the economy geared down, unemployment rose again to double digits. The jobless rate rose to 11.6 percent in October 2018, the highest number of the last fifteen years. Youth unemployment rose to 22.3 percent from 19.3 percent in 2017. One fourth of those under 24 years are now neither in employment nor in education.

CONCLUSIONS: Affluence – being able to purchase the latest Apple iPhone, ride a luxury car, to live in a new and modern house – has vanished like a mirage. The only way back to the glorious days of the last decade is a shift in the monetary policy of Fed. But with the current dynamics of the American economy, this seems highly unlikely. “We would hope that was a very unusual intervention and one that we would not frequently be relying on in the future,” Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen said in 2017, when declaring the end of quantitative easing.

The diehard supporters of the AKP are inclined to believe that the economic crisis is organized by the “interest lobby,” by international power elites who supposedly aim to subvert the revival of Turkey as a world power. Erdoğan has a receptive audience among diehard Islamists and nationalists. But the AKP also has a non-ideological supporter base that will be less receptive to such ideological overtones. The former shantytown dwellers that shifted to the AKP as they became middle class did so in the expectation that they could look forward to a prosperous future. Bleak economic prospects will turn them away from the AKP. Get ready for substantial drops in AKP votes in the upcoming municipal elections.

AUTHOR’S BIO:

Barış Soydan is a columnist for the Turkish news site T24. He has been editor-in-chief of TurkishTime, of Power, of Turkish business magazines and managing editor of the daily Sabah.

Picture credit: kremlin.ru via Wikimedia accessed on February 11, 2019