BACKGROUND: Even though it played no role in the putsch itself, from a geographical perspective, the southeast of Turkey bore the brunt of the steep rise in human rights abuses under the State of Emergency that was introduced following the failed coup attempt of July 15-16, 2016. Arbitrary detentions, torture, physical maltreatment and extrajudicial executions rose to levels not seen for over 25 years. Kurdish charities, cultural associations and media outlets were closed down. Hundreds of members of the HDP and its sister party, the Democratic Regions Party (DBP), were imprisoned on charges of aiding the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Erdoğan also used extraordinary presidential powers granted to him under the State of Emergency to dismiss the DBP mayors of 94 of the 102 local administrations that its predecessor, the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP), had won in the most recent elections in March 2014. In their place, Erdoğan appointed state officials, known as “administrators”, who dismissed thousands of municipal employees and replaced them with supporters of Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP).

The State of Emergency was imposed at a time when the southeast was still traumatized by the urban clashes that wracked the region from late summer 2015 through spring 2016, as the PKK sought to bring its long-running rural insurgency into the cities – in the form of urban bombings in western Turkey and the establishment of no-go areas in Kurdish towns and cities. Both were major strategic errors. The urban bombing campaign alienated many Turkish liberals and was a gift to Erdoğan. He used it to retrospectively justify both his abrogation in March 2015 of the dialogue he had initiated with imprisoned PKK founder Abdullah Öcalan in late 2012 and his disproportionate response to the murder of two police officers in July 2015 – killings initially claimed but subsequently denied by the PKK – after which Erdoğan launched a massive military crackdown in the southeast, to which the PKK responded by escalating its own attacks. In the towns and cities in which the PKK attempted to create no-go areas, the Turkish security forces watched and waited as local youths – many of them still in their mid-teens – reinforced by trained PKK militants dug trenches and stockpiled weapons. Then they unleashed their overwhelming military superiority, including tanks and artillery, against both the armed youths and the non-combatants amongst whom they were embedded. Large swathes of Kurdish cities areas were razed to the ground, historical sites looted and vandalized, and even undamaged apartment blocks punitively demolished – and peppered the surrounding areas with Turkish flags to demonstrate to the local populace the bludgeoning power of the Turkish state.

Even before the State of Emergency was lifted in July 2018, the Turkish state had begun to adopt a lower profile in the region – reducing the number of checkpoints on roads and the presence of heavily armed police paramilitaries on the streets, while increasing technical surveillance. Through 2018, as Erdoğan looked ahead to the March 2019 local elections, the administrators used their access to the state’s financial resources to launch “beautification” projects in the cities they controlled. But the emphasis has been on immediate visibility – such as better sidewalks and street-lighting – rather than less ostentatious, bur arguably more urgently needed initiatives to address the region’s social and economic problems. Nor have the administrators eased the official and unofficial restrictions on Kurdish language and culture. In January 2019, the AKP even named Cumali Atilla, the state-appointed administrator in Diyarbakır, as its candidate for mayor of the city in the forthcoming elections.

In the immediate aftermath of the fighting in the cities, many Kurds – including PKK supporters – were bitterly resentful of the organization for knowingly exposing both the combatants and the non-combatants in the no-go areas to a devastating assault by the security forces. Yet, when the fighting in the cities was over, instead of launching “hearts and minds” programs, Erdoğan used the State of Emergency to try to tighten the state’s grip on the region through repression and intimidation. The result has been not only to deepen Kurdish alienation from the Turkish state – which the administrators’ beautification projects have done nothing to allay – but from Turks.

IMPLICATIONS: In the June 2015 general election, a significant proportion of Turkey’s small but highly vocal liberal intelligentsia voted for the HDP. At the time, ensuring that the HDP overcame Turkey’s 10 per cent electoral threshold and entered parliament was seen as the most effective way of preventing the AKP from winning sufficient seats to enable Erdoğan to introduce an executive presidential system – although he subsequently compensated by enlisting the support of the Turkish ultranationalist Nationalist Action Party (MHP). Even if it was at least partly tactical, Turkish liberal support for the HDP did at least serve as a bridge between Turks and Kurds. This has now gone. Not only did many liberal Turks abandon the HDP in the general elections of November 2015 and June 2018 but – from the Kurdish perspective – they remained largely, though not completely, silent during the fighting in the cities in 2015-16 and even more so during the crackdown in the southeast under the State of Emergency. Consequently, there is a widespread perception in the southeast that liberal Turks are only sympathetic to the plight of the Kurds when it serves their own purposes – and other Turks not at all.

Although there are differences as to the form it should take – whether devolution, autonomy or full independence – there has been a marked increase in the number of Kurds who believe that their future lies in greater control over their own affairs. The shift can also be seen in the HDP’s strategy for the March 31 local elections, which it will contest in its own name rather than that of the DBP. Previously, the HDP had looked for electoral partners to the Turkish left. On January 7, 2019, the HDP announced the formation of a new eight-member alliance. Although the alliance contains some left-wing Kurdish parties, it also includes conservatives and the Islamist Kurdish Islamic Movement (Azadi). The only characteristic that all eight members of the alliance share is an explicit commitment to Kurdish. Four of the parties have the word Kurdistan in their names.

During his campaign for the local elections, Erdoğan has repeatedly sought to justify his targeting of the HDP and DBP on the grounds that they are controlled by the PKK. This is misleading. A large proportion of both HDP/DBP officials and their supporters are undoubtedly sympathetic to the PKK and the organization has long exercised considerable influence in – though never total control over – the two parties. For example, low-ranking HDP/DBP officials are often the first point of contact for youths wishing to join the PKK and it is an open secret in the southeast that, while the local administrations were controlled by the DBP, the PKK was often involved in decisions regarding the awarding of municipal contracts. But Erdogan has indirectly enhanced the PKK’s influence in the parties by indiscriminately targeting both those who are close to the organization and those who are not. For example, the former HDP co-chair Selahattin Demirtaş – who was sometimes prepared to defy the PKK and is disliked and distrusted by the organization’s leadership as a result – has been imprisoned since November 2016.

Nor has Erdoğan hesitated to use his control of the judicial system to try to suppress Kurdish parties which are rigorously opposed to the PKK and HDP. For example, the small Kurdistan Freedom Party (PAK), which is sympathetic to the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) in northern Iraq and whose members were aggressively targeted by the PKK in the past, now faces a closure case. In a bizarre throwback to the pre-AKP regime’s denial that Kurds even exist, the indictment against PAK alleges that its defense of the right of Kurds to establish their own state constitutes an attempt “to create a race”.

As a result, for the Kurds of the southeast, the March 31 elections are less about whether or not the HDP-led alliance would be able to provide good local governance – even if Erdoğan allowed it to take office – and more an act of defiance and an assertion of their own Kurdishness. But there is little hope that the situation will improve in the foreseeable future, merely a stubborn determination to endure.

CONCLUSIONS: Although it is likely to step up its attacks in the mountains of southeast Turkey as the winter snows continue to melt, the PKK is constrained by one of the periodic shifts in the balance of power on the battlefield, currently as a result of the Turkish security forces’ increased used of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). The PKK is also aware that a return to the urban bombing campaign in western Turkey in 2015-16 could jeopardize the military alliance between its Syrian affiliate, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), and the United States. Nor can it afford the loss in popular support that would result from any new attempt to turn the towns and cities of southeast Turkey into battlegrounds.

Even though the PKK has maintained back channels to the government in Ankara, there is little prospect of an imminent return to negotiations, particularly while Erdoğan remains in power. In 2013, in response to the Gezi Park Protests, Erdoğan shifted from trying to broaden his support base to trying to deepen it, inculcating a siege mentality amongst his supporters and increasingly turning them against the rest of Turkish society, whom he portrays as active participants in Western plots to try to undermine him.

Since 2013, Turks have gone to the polls at least once every year. The only exception was in 2016, when the country was rocked by the still largely unexplained attempted putsch. The elections and the coup attempt were politically and economically destabilizing. But they also served as a form of release, as the hatred and paranoia were briefly transformed into triumphalism at the defeat of another imagined foreign conspiracy – only for Erdoğan to begin stoking them again in the run-up to the next short horizon.

After the local elections, Turks are not due to go to the polls again until June 2023. From one perspective, this should allow Erdoğan the time and political space to address the Kurdish issue. But not only has he now made his political survival dependent on raising social tensions but his rhetoric is becoming increasingly extreme, and it is questionable whether he is psychologically capable of becoming more moderate and conciliatory – both of which are prerequisites for a resolution of the Kurdish issue; and the longer addressing the issue is delayed, the greater the concessions the Turkish state will eventually have to make in order to resolve it.

AUTHOR’S BIO:

Gareth H. Jenkins is a Non-resident Senior Fellow with the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center.

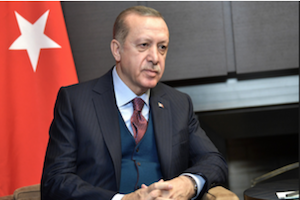

Picture credit: kremlin.ru accessed on March 27, 2019