BACKGROUND: When Atatürk founded the Turkish Republic, he embarked on one of the most ambitious social engineering projects of the twentieth century, seeking to transform a multiethnic predominantly Sunni Muslim society in which religion was the primary determinant of identity into a secular Turkish nation. His reforms were implemented by an authoritarian one-party state, using legislative reforms, official discourses and a tightly-controlled education system. Rather than simply seeking to separate state and religion, Atatürk sought to purge Islam from the public space.

However, low levels of literacy and access to education meant that the inculcation of Atatürk’s doctrines – or “Kemalism” – primarily penetrated the urban educated elite and had only a limited impact in the countryside where the majority of the population lived. The introduction of multiparty democracy in 1946 was soon followed by rapid urbanization, which increasingly brought both the rural population and their values into the cities. Even though Kemalism continued to be inculcated through official discourses and the education system, the result was a string of populist governmental concessions to conservative values – and eventually even the emergence of Islamist political parties.

By the late 1990s, although the Turkish Constitution still maintained that Turkey was a secular state, in reality it was more of a hybrid regime, sometimes paradoxically so. For example, the inculcation of Sunni Islam had become compulsory at every level of the education system for Sunnis and non-Sunnis alike. This was not regarded as a violation of secularism. But Sunni female university students were forbidden from covering their heads on the grounds that this did violate secularism.

Similarly, although Turkey was theoretically a multiparty democracy, in practice politics were conducted in the shadow of the Turkish military. In the fifty years before the Justice and Development Party (AKP) first took office in November 2002, the Turkish military intervened four times to oust elected governments. However, although it has now become commonplace to ascribe all of the flaws of the pre-AKP Turkish political system to the system of military tutelage, the reality is more complex.

The military interventions – particularly the brutal three years of military rule that followed the 1980 coup – were undoubtedly inimical to the development of a fully-fledged democracy. But neither does the record in office of successive civilian governments suggest that they would have introduced a fully-fledged democracy if the military interventions had not taken place. Indeed, it was arguably the failure of civilian politicians to provide political or economic stability – much less create a functioning democratic system – that sustained the military’s involvement in politics. In a political system with few checks and balances, many Turks even regarded the political role of the military as a counterweight to the frequent chaos and crises wrought by civilian governments. Public disillusion with politicians increased still further in the 1990s with a series of corrupt and incompetent coalition governments which not only failed to provide political stability but whose economic mismanagement culminated in February 2001 in the worst economic collapse in modern Turkish history.

In this context, the timing of the foundation of the AKP in August 2001 was fortuitous. The leaders of the AKP had all started their political careers in hard-line Islamist parties led by Necmettin Erbakan (1926-2011). But they managed to distance themselves from Erbakan’s legacy not only by breaking away to form their own party but by attracting a broad spectrum of support, ranging from former leftists disillusioned with the mainstream secular parties to Islamist elements opposed to Erbakan, such as the Fethullah Gülen Movement. The AKP’s leaders publicly espoused a commitment to pluralistic democratic values, refuting suggestions that they had an Islamist agenda and pledging to accelerate Turkey’s bid for EU membership. Although skeptics questioned the AKP’s sincerity, in the November 2002 general election it was the only party that could plausibly claim to offer anything new – and won a comfortable majority in parliament.

During its first term in office, the AKP proceeded cautiously, focusing on nurturing economic recovery and avoiding antagonizing the staunchly secular Turkish military in the sincere belief that doing so could trigger a coup. Although the AKP introduced some liberalizing reforms that were anathema to hard-line Kemalists – such as easing the restrictions on the expression of a distinct Kurdish cultural identity – it ensured that they came within the scope of furthering Turkey’s bid for EU membership. It was only in 2007, when it secured a second term in office after successfully defying an attempt by the military to intimidate it into abandoning its plans to appoint Abdullah Gül to the presidency, that the AKP finally understood what the country’s generals had known for years – namely, that their once overweening political influence had been reduced to little more than bluff and bluster. For the first time, the AKP and Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan realized that they were not only in office but in power.

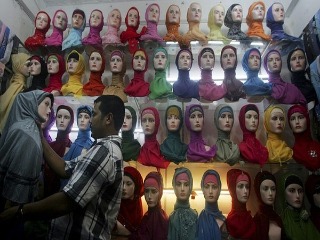

IMPLICATIONS: Over the last six years, the AKP has pursued an increasingly explicit Islamist agenda. Erdoğan has made no secret of his desire to conduct his own social engineering by amending the education system to ensure the creation of “pious younger generations” and reshaping the public space in accordance with his own Sunni Muslim values. Although some of the changes have been dressed in the language of freedoms and human rights, in practice it has been Sunni Muslims who have benefited. For example, on September 30, 2013, Erdoğan announced the abolition of the headscarf ban on the grounds that it violated wearers’ human rights. But the inculcation of Sunni Islam remains compulsory at every level of the education system, even for members of Turkey’s large heterodox Alevi community.

More insidious has been the use of official discourses to impose conservative Muslim values. For example, AKP officials – including Erdoğan himself – have repeatedly made it clear that they regard women’s primary functions as being mothers and homemakers, protected by and subordinate to men. Although it has not introduced any legislation explicitly discriminating against women, there is no question that the limited progress made on gender equality before the AKP came to power has not merely halted but is now in reverse.

Similarly, the longer the AKP has remained in power, the more authoritarian and intolerant it has become. Dozens of journalists are in jail, while hundreds more have been forced from their jobs by pressure from the government. Not surprisingly, self-censorship has become widespread. Although it is always possible to find a point in Turkish history where matters have been worse or better, there is no doubt that the media is considerably less free now than it was during the AKP’s first term – and the situation is still deteriorating.

Equally disturbing has been the plethora of highly politicized court cases – such as the notorious Ergenekon and Sledgehammer investigations – that have been instigated against opponents, rivals and critics of the Islamist Movement. Most are being driven by activists from the Gülen Movement, who have also taken the lead in trying to intimidate into silence those who have questioned the conduct of the cases. Indeed, the abuses of due process and the regularity with which evidence has clearly been fabricated have raised serious concerns not only about the Gülen Movement itself but also about the rule of law in Turkey. Although the Turkish judicial system has always been highly politicized, the levels and flagrancy of the abuses now taking place are without precedent.

Concerns about the rule of law have been exacerbated by the increasing concentration of political power in Erdoğan’s own hands. There is no reason to suppose – as is sometimes claimed – that he has become more radical in his policy agenda. On the contrary, the measures and values he now advocates are virtually identical to those he espoused before he came to national attention in the late 1990s. What has changed the longer Erdoğan has remained in office is his confidence in his ability to implement them. Indeed, after three successive election victories, Erdoğan now seems to believe that he embodies the national will.

Erdoğan’s relentless self-belief means that policy-making has been largely deinstitutionalized. Almost all major policy decisions are taken by Erdoğan himself within a closed circle of sycophantic advisers. The process has already resulted in a number of fiascos, particularly in foreign policy. For example, his disastrous policies towards the Middle East were largely based on the conviction that the region’s Sunni Muslims looked to Turkey in general – and to himself in particular – for leadership. He blithely ignored warnings by the seasoned diplomats at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs that reality was considerably more complicated.

Similarly, Erdoğan seems unaware that a crisis is looming over the Kurdish issue. Instead, he appears genuinely convinced that a combination of minor cultural concessions and a willingness to engage in an indirect dialogue with imprisoned Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) founder Abdullah Öcalan should be sufficient to satisfy Kurdish nationalists and persuade the PKK to lay down in its arms. In fact, a decade ago, such concessions would have been considered revolutionary. But Kurdish nationalist demands have now risen to the point where only full cultural rights and the granting of a degree of autonomy to the predominantly Kurdish southeast of Turkey are likely to prevent the PKK from abandoning its current ceasefire and returning to violence when the winter snows melt in spring 2014.

CONCLUSIONS: In retrospect, it is clear that the AKP’s first term in power was not part of a transition to a pluralistic democracy but an interregnum. Over the last six months, Erdoğan’s growing autocratic authoritarianism – particularly his heavy-handed attempts to crush the Gezi Park protests that swept Turkey during the summer – has done irreparable damage to his international credibility. It has also weakened him domestically. Some of his traditional support base has been loosened, but not yet detached – not least because the failure of the opposition parties to offer a convincing alternative means that there is still nowhere for it to go.

Indeed, increasingly the opposition to Erdoğan is now coming from inside the Islamist movement, from his former colleague Abdullah Gül and his erstwhile allies in the Gülen Movement. Yet, although both are considerably less abrasive than Erdoğan, in terms of values and ideological agendas there is little to choose between them. It is also doubtful whether either could heal the deepening fissures in Turkish society and reassure the diverse groups – ranging from secularists to Alevis and Kurdish nationalists – who are feeling under increasing threat from the AKP’s attempts to reshape Turkish society according to pious Sunni Muslim values and lifestyles. Indeed, although they are less hated than Erdoğan, Gül and the Gülen Movement’s espousal of similar values means that they are generally regarded not as a solution but as part of the problem.

Gareth H. Jenkins is a Nonresident Senior Fellow with the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center.