BACKGROUND: Turkey and Azerbaijan enjoy strong strategic relations on many levels which are based on ethnic and cultural kinship. Apart from close partnership in political and energy fields, the two countries cooperate in the military sphere, including joint army exercises and military technology transfers. The cornerstone of their security and military alliance is an Agreement on Strategic Partnership and Mutual Support signed in 2010 which obliges the signatories to support each other in case of outside aggression and envisages closer military cooperation between them. Turkey gave Azerbaijan unprecendented support earlier this year during the July cross-border clashes with Armenia and during the recent war in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Turkey's unusually assertive stance was only partially motivated by the need to help its strategic ally to break a long stalemate in Nagorno-Karabakh. It also reflects Ankara's broader foreign policy ambitions in its neighborhood that includes the Black Sea region and South Caucasus. As a part of this strategy, Ankara has sought to influence the outcome of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and has recently started to pursue tighter relations with Georgia and Ukraine. Assertive posturing across the region is also a part of domestic policy calculations for the Turkish regime, as nationalist muscle-flexing may divert attention from the severe economic crisis that Turkey is currently going through. Moreover, the policy of assisting Azerbaijan is supported by large swathes of Turkish society and across the political spectrum.

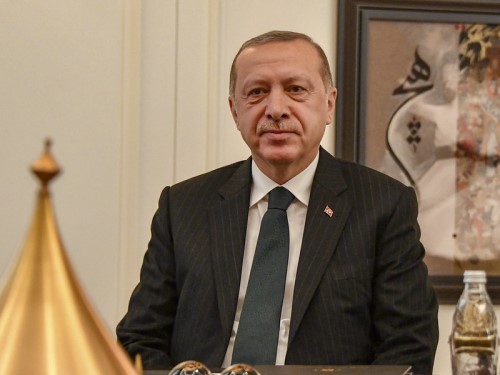

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has used unusually harsh rhetoric against Armenia and his unequivocal support for Azerbaijan has been endorsed by all opposition parties, except by the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democracy Party (HDP). Turkey reportedly deployed military personnel to Azerbaijan to support and coordinate the offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh. The Russian newspaper Kommersant claims that about 600 Turkish personnel, with high-ranking officers among them, were present in Azerbaijan and its Nakhchivan enclave, incuding military advisors, drone operators and dozens of military instructors.

Turkey's extensive military and technical support for Azerbaijan during the war in Nagorno-Karabakh tipped the scales in Baku's favor. Following the first clashes in July, Turkey conducted unusually large-scale military drills with Azerbaijan and, as President Ilham Aliyev confirmed, left a few of its F-16 warplanes on its territory for deterrence purposes. The Armenian Ministry of Defense claims these fighter jets were in fact used in combat, a claim denied by Turkey and unsupported by evidence.

A crucial element of Turkey's military assistance to Azerbaijan has been the transfer of military technology and strategic advice. The sales of Turkish military hardware to Azerbaijan had in fact surged in the months before the outbreak of the war. These included unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) – a product of Turkey's rapidly expanding drone industry, rocket launchers and other weapons.

Turkish, but also Israeli and Russian combat and reconnaissance UAVs transformed the battlefield conditions in Nagorno-Karabakh and contributed to Azerbaijan's fast military gains. Relatively low-cost drones left Armenian ground forces severely exposed, overwhelmed their air defense systems, and destroyed tanks and artillery. The Turkish tactical long endurance Bayraktar TB2 drone stood out among Azerbaijan's drone fleet, offering Baku a substantial edge on the battlefield. This multipurpose attack UAV proved highly effective in combat and reportedly took out dozens of Russian-made air defense systems – mainly 9K33 OSA and 9K35 Strela-10 – used by the Armenian forces.

Ankara stands to land lucrative military deals as several countries have shown interest in purchasing its drones after their impressive performance in Syria, Libya and now Nagorno-Karabakh. Recently, Kazakhstan, Serbia and Ukraine expressed their interest to purchase Turkish Bayraktar TB2 UAVs.

Not only sophisticated weaponry, but also innovative strategy and tactics contributed to Azerbaijan's edge on the battlefield. Experts point out that Azerbaijan's drone operation in Nagorno-Karabakh bears a strong resemblance to Turkey's Operation Spring Shield carried out in Syria's Idlib province in early 2020 against the the Syrian Armed Forces. Hence, they conclude that Turkey gave Azerbaijan access not only to military technology, but also shared its drone warfare strategy with it. Apart from that, Turkey shared commando tactics that have been employed by American and other NATO troops in Afghanistan with Azerbaijan. Small, specialized Azerbaijani commando teams inflitrated the territory, captured strategic points and coordinated the attack of land and air forces.

Controversially, some media outlets have claimed that foreign mercenaries recruited from Syria and Libya were deployed by Turkey to the conflict zone. Ankara and Baku, though, promptly rejected these accusations.

IMPLICATIONS: Turkey is a main beneficiary of the Nagorno-Karabakh trilateral armistice agreement that was signed by Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia on November 9, for the first time getting a direct land connection with Azerbaijan. The agreement envisages the construction of a road that will link Azerbaijan with its exclave Nakhichevan and further on with Turkey through Armenian territory that will be guarded by the Russian military. This first land route connecting Turkey and Azerbaijan will have economic implications, potentially boosting trade relations between the two allies and facilitating supplies to the Nakhchivan exclave. But even more importantly, it will have geopolitical ramifications, as it will provide Turkey with a gateway to the Caspian Sea and Central Asia, invigorating its ties with the Turkic nations of Central Asia, which has been Ankara's ambition since the fall of the Soviet Union.

However, more immediately, Turkey aims to be involved in shaping the post-ceasefire security design in Nagorno-Karabakh on par with Russia. Ankara has recently proposed to create a new format for peace negotiations which would include Turkey, Russia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Also, Azerbaijan has put forward an idea to include Turkey as a new co-chair in Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe's (OSCE) Minsk Group, which is a multilateral forum for the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

Foremost among Turkey’s objectives has been to deploy peacekeeping forces in Nagorno-Karabakh. In November, the Turkish parliament adopted a resolution that allows for the deployment of troops and civilian personnel for a year, to a location that Azerbaijan will determine. Turkey will also send explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) military teams to Azerbaijan to clear mines and other explosive devices in the territories retaken from Armenians.

These moves were made amidst Turkish-Russian disagreements on the details of Turkey's engagement in post-war security arrangements in Nagorno-Karabakh. The ceasefire accord does not make any mention of Turkey, and envisages that Russia will be the sole peacekeeping force in the region. However, separate bilateral arrangements between Moscow and Ankara have granted Turkey a shared role with Russia in the joint monitoring centre, a subsidiary body mentioned in the armistice deal which will be responsible for overseeing the ceasefire. Meanwhile, Russia has been visibly opposed to Turkey assuming a peacekeeping role as an equal partner. Russian officials firmly responded to Turkey's announcements of sending peacekeepers to the South Caucasus by underlining that Turkish troops will not be deployed in Nagorno-Karabakh, but will be present in the monitoring centre only.

After weeks of diplomatic back and forth, in early December Moscow and Ankara signed the separate agreement on joint monitoring centre, which lays out detailed technical framework. The center's location was the main bone of contention between Turkey and Russia. Reportedly, Russia intended to keep the centre far from Nagorno-Karabakh, unlike Turkey which preferred to locate it as close to the region as possible. Eventually, the centre will be located in Azerbaijan's district of Aghdam, which was recently handed over to Baku by Armenia following the November ceasefire.

CONCLUSIONS: Unsurprisingly, Russia has no intention of sharing influence with Turkey in the Caucasus, while the presence of Turkish soldiers in Nagorno-Karabakh and near Armenian settlements would have been utterly unacceptable for Armenia. Thus, offering Turkey the role that it covets would have made it impossible for Russia to uphold its position as a mediator in the region and as a protector of Karabakhi Armenians.

Yet even though it has been relegated by Russia to the lesser role in the peacekeeping efforts, Turkey has nonethelss gained a much-desired military foothold in the south Caucasus, and even more importantly, a direct gateway to the Caspian Sea and Central Asia that may in time prove crucial. Turkey’s extensive military involvement in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, supporting Azerbaijan, has already payed off and is set to have far-reaching geopolitical implications.

AUTHOR’S BIO:

Natalia Konarzewska ( This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. ) is a graduate of University of Warsaw and a freelance expert and analyst with a focus on political and economic developments in the post-Soviet space.

Image Source: United States State Department via Flickr. Accessed 12.30.2020